Thinking Big — Roads and Railroads to Siberia:

Visions of the Bering Strait Tunnel

Crossing the Strait:

Engineering Railway Ambition Across Centuries

The vast expanses of Alaska and northern Canada—and the North's underdeveloped road and rail systems—have long seemed an unnatural limitation on the region's growth. For generations, entrepreneurs, engineers, and political leaders have sought to correct this imbalance and bring the region in line with the transportation standards of the rest of North America.

The most ambitious of these visionaries have looked even farther: proposing transportation corridors linking western Alaska with Siberia. Sixty-five years ago this month, for example, representatives said to be acting on behalf of New York bankers proposed building a road from Edmonton, Alberta, to Atlavik near the mouth of the Mackenzie River in Canada's Northwest Territories—eventually connecting to Siberia via Alaska's North Slope. Alberta's Minister of Public Works took the proposal seriously, though noting that "there are many obstacles."

More recently, a Russian official revived the idea of a railroad connecting Siberia and Alaska via the Bering Strait. In 2001, shortly after becoming Chair of the U.S. House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, Alaska Representative Don Young urged his constituents to think boldly: "There's no reason we can't have a railroad to Russia."

These bold ideas echo the insights of historian Terrence Cole, whose compelling exploration of this very subject was published in the journal Alaska History at the end of the Cold War, just before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

What follows is Terrence Cole's original article, presented here (without endnotes and illustrations) as it appeared in the Fall 1990 issue. For the full version, please refer to AHS Publications via the Alaska Historical Society.

The Bridge to Tomorrow:

Visions of the Bering Strait Bridge

Bering Strait, the narrow gap between the eastern and western hemispheres, today blocks the path of one of the oldest and most important transportation corridors in the world. Starting tens of thousands of years ago, Native Americans migrated in waves across a huge Bering Land Bridge which once connected Alaska and Siberia. Eventually these wanderers spread over all of North and South America. Melting glaciers and rising oceans at the end of the last ice age covered the land bridge with water, and left a tantalizingly narrow gap between two worlds, which has stood as an unsolved engineering challenge ever since. The missing link between the eastern and western hemispheres has inspired more wild flights of fancy by inventive minds than any natural obstacle or water body on earth. Ever since the true contours of the map were first known, the strait has pulled like a magnet, attracting dreamers with plans to tie the world together.

The distance across Bering Strait from Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, to Cape Dezhneva, Siberia, is only forty-four miles, about twice the length of the narrowest part of the English Channel and approximately equal in length to the Panama Canal. Near the center of Bering Strait lie the two Diomede Islands, which straddle the boundary between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., and the International Date Line between today and tomorrow. On a clear day, standing on the American island of Little Diomede, one can see the Soviet island of Big Diomede about two miles to the northwest.

Since the onset of the Cold War in the 1940s, there has been virtually no transportation or communication across the narrow space between Alaska and Siberia. The back doors of the two superpowers have been frozen shut for nearly forty years. But Mikhail Gorbachev's rise to power and his attempt to reform the Soviet system with "glasnost" and "perestroika" have probably been applauded as loudly in Alaska as anywhere in the world. Alaskans were quick to see the possibility for increased transportation, communication, commerce, and scientific and cultural exchanges with their neighbor to the west, and have tried to capitalize on the changes in the U.S.S.R.

Nome real estate salesman Jim Stimpfle is head of the Nome CCCP, the Committee for Cooperation, Commerce and Peace. Not all of his efforts to make peace with the "evil empire" have been smooth. In the winter of 1986–87, Stimpfle launched a weather balloon at Nome loaded with gum, tobacco, and messages for the people of Siberia. The balloon crashed about three miles offshore. An Eskimo man fishing nearby could salvage only the chewing gum. Stimpfle's campaign for a Friendship Flight between Alaska and Siberia attracted international attention when a jet load of Alaska Natives, business leaders, journalists, and government officials, including Alaska Governor Steve Cowper and U.S. Senator Frank Murkowski, made a brief trip from Nome to Provideniya, Siberia on June 13, 1988. Now tour ships have requested to include stops in Siberian ports on future cruises and restrictions on air travel have been lifted. Delegations from the Soviet Union have toured Alaska, including a party led by Gennad Gerasimov, chief spokesman for Gorbachev. Gerasimov was warmly received all across the state in the spring of 1988 when he told Alaskans that one of the reasons for the October Revolution was "that the czars were so silly to have sold Alaska."

The great interest in Alaskan–Siberian ties inspired a Juneau man to recommend that the State of Alaska replace the slogan "The Last Frontier" on its license plates with "Gateway to Asia." It is too early to tell if the barriers between Alaska and Siberia will continue to melt, but Gorbachev's reforms have rekindled interest in the nineteenth-century dream of tying the continents together, and revived an age-old scheme to make the Bering Strait a true international crossroads.

The first serious plan to span the Bering Strait was the attempt by the Western Union Telegraph Company in the 1860s to stretch an overland telegraph line around the world. It was a project worthy of Jules Verne. Believing that a submarine cable across the Atlantic was impractical, Western Union sent out survey and construction crews in 1864 and 1865 to find a route for a five-thousand-mile-long telegraph line, stretching from the United States to the mouth of the Amur River in Siberia.

The Western Union Telegraph project was abandoned after Cyrus Field successfully laid a submarine cable across the Atlantic in 1866, but the seed of the idea that the Bering Strait could link the world had been planted. To an era which witnessed the "miracle" of the Suez Canal, completed in 1869, and the beginnings of the Panama Canal, the dream of a Bering Strait Bridge seemed entirely possible thanks to the great wonder of the age: the railroad.

The lure of long distances and far away places has always been part of the magic of the railroad, and during the heyday of railway construction in the second half of the nineteenth century, politicians, promoters, cranks, and inventors from across the United States drew up plans for round-the-world railroads via the Bering Strait. Skeptics, according to a doubtful man in Cincinnati, thought such an idea had to be "an illusionary project emanating from a mind diseased" but believers in the future just pointed to the globe. The San Francisco industrial journal Wood and Iron stated in the mid-1880s, "An examination of a map of the Pacific coast of America, from San Francisco to the extreme northwestern point of Alaska, where it is divided by only a narrow strait from the mother continent, Asia, will easily convince the most skeptical and conservative reader that the scheme of an Inter-oceanic railway . . . is not illusionary, but of a decidedly practical nature."

In the 1870s and 1880s, John Arthur Lynch of Washington, D.C. pestered the U.S. Senate, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, and any government official he could find with a scheme that Lynch said had become the "permanent object" of his life: construction of a railroad to Alaska, which could connect by steamship with Siberia, Japan, and China. Lynch claimed that such a railroad would give the United States "direct commercial intercourse with the vast population of Asia."

In response to a petition from Lynch, a bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate in 1886 to "open an overland and commercial route between the United States, Asiatic Russia and Japan." The chairman of the Committee on Foreign Relations referred the bill to the Interior Department for a recommendation. The noted explorer and director of the U.S. Geological Survey, John Wesley Powell, looked into the idea for the government. Powell stated that building a railroad to the doorstep of Asia would pose no "greater obstacles . . . than those already Overcome in transcontinental railroad building." The geologist soberly added, however, that no one had asked him to "express any opinion as to the wisdom" of the project.

The Senate failed to take any action. The U.S. government's refusal to commit its resources to map or survey a railway route to Alaska in 1886, as it had done for the transcontinental lines to the Pacific, did not deter those whose compasses pointed towards Bering Strait. Furthermore, changes in Russia indicated that the time was right for Americans to take the initiative. Czar Alexander III had ordered exploratory surveys in 1887 for an extension of the Russian railway system eastward into Siberia (which culminated in the decision to begin construction on the Trans-Siberian Railway in 1891). The San Francisco Bulletin noted in 1888 that whether or not the much discussed rail link via Bering Strait was ever built, Russian railway construction through Siberia to the Pacific Coast would make the people of Siberia potential customers for California businessmen.

That year Railway Age carried a dispatch from St. Paul announcing the "stupendous scheme" of railroad engineers from Chicago and Minnesota, who planned to build a railway from the Twin Cities to Peking via Bismarck in the Dakota Territory, and other intermediate destinations. "This project looks huge. It is," the report stated, "and a few years ago would have been deemed a crazy idea and impossible of execution. But scarcely a better country for railroading could be found, with comparatively small exceptions." Bering Strait, according to these midwesterners, who had most likely never been near it, was a shallow and narrow body of water that was "midway dotted with islands," and "can ultimately be bridged, though temporarily a crossing will be made in boats."

Eternal peace and economic prosperity were the twin benefits that most visionaries saw forthcoming from the round-the-world railway. William Gilpin, the first territorial governor of Colorado, gave the most eloquent explanation of this concept in a book he published in 1890 entitled The Cosmopolitan Railway, Compacting and Fusing Together All the World's Continents. Gilpin claimed that he had studied the geography of North America for fifty years, and that he had gradually conceived the plan for what he called the "Cosmopolitan Railway." It became an obsession with him.

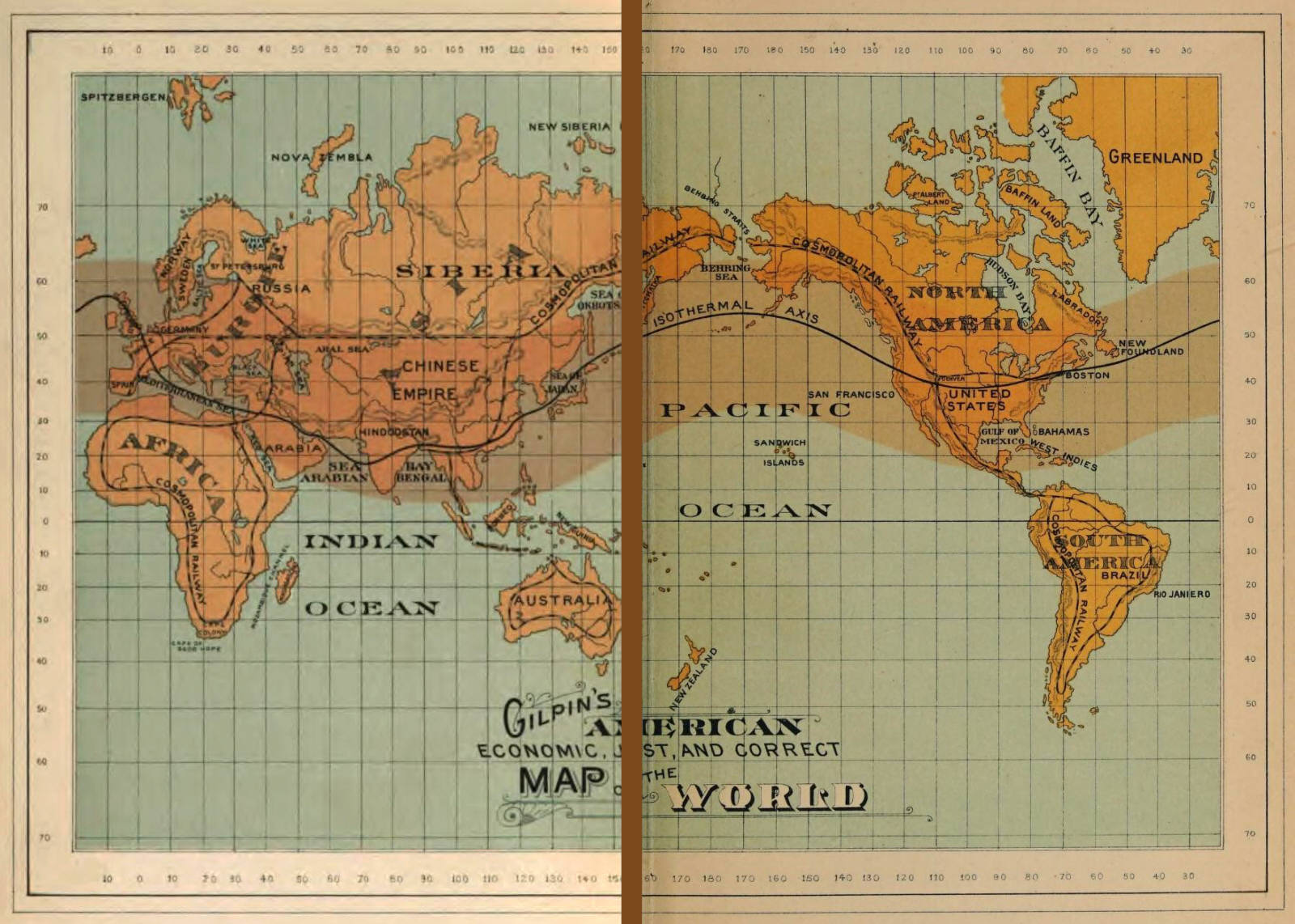

Click the image to zoom.

"The idea forced itself more and more upon my mind," he wrote, "of a widely extended railway system. This system should not only traverse the continent from sea to sea, but should continue its course north and west across the strait of Bering; and across Siberia, to connect with the railways of Europe, and of all the world. The more I investigated, the more practicable the plan appeared, until the certainty of its consummation at no far distant day became with me a settled conviction."

Gilpin's volume on the Cosmopolitan Railway was an elaboration of his many geographical and climatic theories which, he thought, explained all of human history. He predicted the Cosmopolitan Railway was the key to launching the world on the track to a higher level of civilization in which his adopted hometown of Denver would be the Rome of the coming centuries, and a worldwide currency, a worldwide language, and a worldwide system of weights and measures would be adopted. A map in his book—modestly labeled as "Gilpin's American, Economic, Just and Correct Map of the World"—pictured Denver as the railway center of the known universe, with the Cosmopolitan Railway linking all the continents. "The truth is," Gilpin wrote, "that this world's highway will so bring together and intermingle all the people of the earth as ultimately in a great measure to obliterate race distinctions and bring about a universal brotherhood of man."

The first man to take a step towards implementing this fantastic vision was Joseph B. Strauss, a young poet–engineer from Cincinnati, who actually designed a bridge to cross the Bering Strait in 1892, two years after the publication of Gilpin's book. Like Gilpin, Strauss was swept along by the beauty and majesty of his grand idea. Where Gilpin saw a railroad to unite the world, Strauss saw the opportunity to build the world's greatest bridge.

Strauss grew up within sight of the famous John Roebling bridge across the Ohio River between Cincinnati and Covington, Kentucky, which served as the model for Roebling's masterpiece—the Brooklyn Bridge. Roebling's bridge inspired Strauss to pursue his two great passions in life: building bridges and writing poetry. When Strauss graduated from the University of Cincinnati in 1892, his senior thesis was a design for a "Gargantuan" railroad bridge across the Bering Strait. He read his thesis at the commencement exercises to an astounded audience. Apparently no copies of Strauss's Bering Strait bridge plans have survived, but some of those who heard him read his paper in 1892 said it was "an impossible and preposterous scheme." Strauss's biographer has claimed that the engineer had a life-long desire to build a work of art like Roebling. During his career, Strauss and his company built more than four hundred bridges, including the Arlington Memorial Bridge over the Potomac River, the Longview Bridge over the Columbia River, and the Golden Gate Bridge, the most beautiful suspension bridge in the world. At the dedication of the Golden Gate in 1937, the Chief Engineer wrote a poem entitled "The Mighty Task is Done," which one could have imagined him reading forty years earlier if his Bering Strait plans had materialized.

Launched midst a thousand hopes and fears,

Damned by a thousand hostile sneers,

Yet, neer its course was stayed.

It was the discovery of gold in Alaska and the Yukon in the late 1890s which made plans for a Bering Strait railway bridge, ferry, or tunnel appear more plausible than the early visions of William Gilpin or Joseph Strauss. Promoters, eager to cash in on the gold strikes, covered the map of Alaska with projected railroad lines, the vast majority of which were never built. Historian C. L. Andrews calculated that during the ten years following the 1898 gold rush, there were on paper forty-eight railroads in Alaska, of which only a handful were more than just paper. Naturally several of the railroad schemes picked up on the old idea of the round-the-world railroad, and many Alaskan communities dreamed that they might one day be a stop on the main line between New York and Paris.

The French had long been interested in the idea of a railroad across Bering Strait. A "French syndicate" formed in the 1890s to investigate the idea received widespread publicity, thanks to the publications of Harry DeWindt, a British travel writer who lived in Paris. DeWindt belonged to the breed of popular nineteenth-century authors who turned out book after book describing their strange adventures in all the corners of the globe, while complaining every step of the way about the hardships they endured for their readers. His 1904 book From Paris to New York By Land detailed his eight-month-long journey across Siberia to Alaska and on to New York which, he claimed, he undertook to determine the feasibility of building a railroad from Paris to New York.

DeWindt stated that his travels convinced him that the idea of a bridge across Bering Strait was absurd. "They might as well talk of a line to the planet Mars," DeWindt wrote, "for the mightiest bridge ever built would not stand the break-up of the ice here for a week." Yet he agreed with Russian engineers who said that the Diomede Islands were perfectly placed for the ventilation of a tunnel which he considered a practical alternative. He believed it would cost less than the construction of the subways then being dug beneath the city of New York. DeWindt predicted the "All-World Railway" would be in operation within a dozen years. "It has passed the stage of a dream," he said in an interview in 1902. "The road will be a single-track one for freight, with sidings, and will enable a train to pull out of Paris, and three weeks later enter New York City."

Following a lecture in New York, President Theodore Roosevelt invited DeWindt to lunch at the White House to discuss the proposed international railway. The President subjected him to a "searching cross-examination" on technical questions which he could not answer, such as "'What fuel would be available beyond the tree line? How would 78 degrees below zero affect iron rails?' 'How many bridges would need construction from the terminus of the existing Siberian railway to Bering Straits, and how deep were the latter at the shallowest part?'" When he could not answer any of these or other questions, Roosevelt asked—with a "faint twinkle in his eye" according to DeWindt—if his guest had in fact actually traveled the entire distance?

DeWindt later wrote that he finally realized that the president regarded the entire railway "as a huge joke—the scheme ... of 'Crooks' or 'Cranks.' Nevertheless, before I left the 'White House,' my host gravely instructed me to reserve him a first-class compartment (and, if possible, a seat in the dining-car) on the first train out from New York for France."

The most dedicated and persistent promoters of the Bering Strait railway crossing might easily have been taken for a couple of cranks. One was a Frenchman named Baron Loicq de Lobel, a self-styled "scientific mining expert" and "chemist," who claimed he was working for the French government when he went to the Klondike for a few months in 1898. De Lobel arrived in San Francisco in October of that year after visiting the gold fields, and announced that he had a plan to sterilize the Dawson City environment and rid it of typhoid and other sickness "by running powerful currents of electricity through the ground, according to the latest French discoveries, to destroy all disease germs."

De Lobel's traveling companion when he landed in San Francisco was John J. Healy. Johnny Healy was nearly sixty years old when he met Loicq de Lobel in 1898. He had been on the move since he left Ireland at age thirteen, but still showed no signs of slowing down. As a teenager, Healy had fought in the Indian Wars. Later he was well known throughout Idaho, Montana, and western Canada for his exploits as a buffalo hunter, miner, trader, and sheriff. Healy arrived in Alaska in the mid-1880s, well in advance of the gold rush. In 1892 he established the North American Transportation and Trading Company which became the second largest trading concern in the Yukon Valley.

De Lobel later claimed that he came up with the plan to build the railroad around the world by himself, while Healy credited the writings of Governor Gilpin as his original inspiration for their enterprise. Starting in about 1901, De Lobel and Healy worked tirelessly on the promotion of the project they called the Trans-Alaskan Siberia Railroad. The key to their plan lay in receiving a land grant from the Czar, which they would use to raise the necessary capital for railway construction. De Lobel spent the majority of his time in New York, London, Paris, or Moscow, raising money and lobbying the Czar for a concession stretching several thousand miles from the Bering Strait to the Trans-Siberian Railway, while Healy took charge of promotion on the American side.

They proposed creating a $200 million company to tunnel the Bering Strait and to build the necessary four thousand miles of railroad track between the United States and central Siberia so the tunnel would go somewhere. Cost estimates for the project ranged from $50 million to as high as $2 billion, but De Lobel and Healy were not discouraged. They predicted the new railway would revolutionize transportation and shift "the world's commercial axis from the Suez canal to Bering Strait." De Lobel said the Trans-Alaskan Siberia Railroad would be "the greatest railroading feat that ever was. No more seasickness, no more dangers of wrecked liners, a fast trip in palace cars with every convenience."

It was widely known that American railroad magnate E. H. Harriman had considered the possibility of constructing a round-the-world railroad, and there are indications—but no solid proof—that De Lobel may have been associated with Harriman. Nevertheless, skeptics refused to take any of it seriously. Scientific American described the plan to tunnel Bering Strait as an "absurd and impossible proposal." The New York Times argued in 1905 that tunneling under Bering Strait might make sense in 1955, fifty years in the future, "but for the moment it is about as practical as a plan to colonize the dark side of the moon."

Another article in the Times in 1906 stated, "Nearly everybody has laughed at the fantastic project of connecting New York with Paris by rail. Only Frenchmen and Russians treat the matter seriously." Czar Nicholas II was one of the Russians who thought the Bering Strait tunnel to be a grand idea. By 1906 the Czar had apparently given his blessing to De Lobel's project, over the opposition of many government leaders, who feared the concessions would lead to the American domination of Siberia. The next year, however, the fears of an American economic invasion won out, and the Czar agreed with his advisors to refuse to grant the concession for the project.

The death of the Trans-Alaskan Siberian Railroad in 1907 was by no means the end of proposals to bridge the Bering Strait. Especially during World War II, when the United States and the Soviet Union were allies in the fight against Hitler, a Bering Tunnel was seen as a possibility for postwar construction and cooperation. After the blazing of the Alaska Highway in 1942, Alaskans were eager to see the road continued all the way to Nome and beyond. By that time it was expected to be an automobile tunnel, enabling motorists to drive between the hemispheres.

The vision of William Gilpin and others, that somehow bridging the Bering Strait can be a sign, a symbol, and even a cause of world peace is still current. In 1968, T. Y. Lin, a civil engineer from San Francisco—sometimes called 'Mr. Pre-Stressed Concrete'—organized a nonprofit corporation called Inter Continental Peace Bridge Inc., whose purpose is to "study, design and construct an intercontinental bridge monument across the Bering Strait between Alaska and Siberia." Lin estimates it might cost about $4 billion to build the bridge, which he says "is trivial when compared with the $600 billion annual defense budget of the two superpowers." "Most certainly," he writes, "the mutual understanding generated by this cooperative undertaking would contribute to a decline in the arms race, so that the bridge cost could be justified many times over. The potentially positive impact on world peace makes its planning and construction a top priority worthy of further consideration."

"With the cold war melting away," a 1990 newspaper article about Lin's Peace Bridge proposal states, the old idea of a Bering Strait bridge "is generating new heat." Recent events in eastern Europe have convinced Lin to propose a $3 million feasibility study of a 4,000-mile-long "Arctic Corridor," stretching from Prince George, British Columbia to Chumikan, Siberia, which would revolutionize world transportation and communications. "Now that relations between East and West are dramatically altered," Lin writes, "the idea of the Intercontinental Transit Corridor and Peace Bridge can become a reality. Indeed, the spirit of Perestroika is part and parcel [of] this proposal."

Lin envisions a 'Magnetic Levitation Train' along the route of the corridor that could carry passengers at speeds of up to 300 miles per hour. Such a corridor would become a global intertie for the movement of oil and gas, electricity, and freight. Where the International Date Line crosses the Peace Bridge, Lin suggests construction of a "Time Span Monument" to enable visitors to "literally straddle 'today' and 'tomorrow.'" Such a monument would become a "tangible expression of the search for peace based on mutual understanding, common goals and international goodwill." It would also be "a beacon as well as a symbolic anchor to the exploration of both inner and outer space."

Lin is not the only one with a persistent vision of the Bering Strait Bridge. Glen Weiss, curator of a New York art gallery, organized "Competition Diomede" in 1989, asking artists and architects around the world to submit bridge designs linking the Big and Little Diomede Islands. As the prospectus for the competition explained: "Simply stated, the only request is to unite two islands, two hemispheres, two countries, two days—the spheres of nature, order, state and time. In a less simple sense, the competition calls for proposals that mark the end of infinite territorial frontiers and the true acceptance of our human existence on a fragile and finite globe." Just as the Berlin Wall once stood as a symbol of a divided world, Weiss believes that a Bering Bridge would represent the goal of universal peace. In response to his proposal Weiss received more than one thousand drawings and plans for bridges to join the Diomedes from about eight hundred artists worldwide. The curator hopes that an exhibition of the bridge designs will eventually tour the globe.

Russian interest in the Bering Strait Bridge surfaced in a recent Novosti Press Agency article by Soviet railway engineer Anatoly Cherkasov. He argued that the spirit of perestroika, plus the completion of the Baikal–Amur Railway, and the construction of a spur line to northern Siberia, "creates, in my opinion, real opportunities for reconsidering the long-forgotten project of building a Siberia–Alaska railway." Admitting that the Soviet government could not afford to spend the estimated twelve billion rubles it would take to build the line, Cherkasov conceded it would need to be an international effort. "I presume that the time has come for the human race to implement the boldest ideas on the earth and in outer space."

Perhaps the roots of the idea that the Bering Bridge needs to be built may rest in one of the oldest American myths, which Henry Nash Smith once called the "Passage to India." Smith wrote that when Thomas Jefferson sent out Lewis and Clark, their expedition captured the American imagination and "established the image of a highway across the continent so firmly in the minds of Americans that repeated failures could not shake it." A manifestation of that myth is the recurring dream of the bridge across the Bering Strait.

SOURCE: Alaska Historical Society

Information in the introduction to this webpage was derived from articles in the Fairbanks Daily News–Miner (March 5, 1936) and the Anchorage Daily News (February 22, 2001).

https://www.alaskahistoricalsociety.org

Obituary: Dr. Terrence M. Cole (1953 – 2020)

Renowned historian of Alaska and Polar History

Read the full obituary at www.interbering.com/Dr-Terrence-M-Cole.html

Article presented by InterBering Management — Fyodor Soloview, President

Russian

Russian